An In-Depth Look at Film Prices, Price Hikes, and the Real Cost of Film.

The following article is an excerpt from SilvergrainClassics print issue 13 that will be available in stores from November 26th 2021. In light of the recent announcement about Kodak film prices, the article was made available early.

Many conversations about film prices these days, both online and at physical gatherings, revolve around the notion that film has become too expensive. Some suggest that those manufacturing it are trying to capitalize off the re-emerged interest in the medium with no regard for their customers — after all, back in the day, film was cheaper. Some even call for a boycott, stating that they feel ripped off.

Are film manufacturers overcharging for their products? In the last three years, film prices have risen dramatically. In some areas, and for some films especially, prices have nearly doubled, depending on region and supplier. With the most recent price increase announced by Kodak Alaris following a price-hike relayed by manufacturer Eastman Kodak in early November 2021, prices will again rise for many beloved emulsions like Tri-X 400. What exactly has led to these increases, and are they out of proportion?

Prices in Perspective: The Last Decades in Review

In the mid- to early-2000s, during the analog crash, film was fighting for its survival. Manufacturers slid down a spiral of plummeting prices to stay competitive just a little longer. But as the market stabilized and companies and photographers started looking to the future of film again, prices began to normalize.

In November of 2019, Kodak Alaris announced a significant increase in film prices, resulting from the surge in demand for film and the subsequently necessary investment in machinery and personnel to keep up with production. At this point, many photographers were understanding and supportive of the price increase, even though some film products experienced a price hike of more than 30%. In November of 2020, however, a second price increase of 15% to 20% was announced to distributors, and the mood began to shift. Since then, many photographers have begun to raise questions about the commercial viability of film and its prospects in the coming years. At the same time, they have started to accuse film manufacturers of cashing in on the regained popularity of analog photography.

It is true: film is no longer a cheap alternative to digital photography (although the debate about which is more expensive overall might still favor analog). Long gone are the days of dirt-cheap “by the bucket” sales of slightly expired stock leftover from the heyday of one-hour-photo-shops. Today, film is in short supply. The withdrawal from or substantial decrease in film production by Fuji means that the overall worldwide production levels have shrunk recently. Coupled with skyrocketing demand for film in the past few years, the pressure on Kodak`s production capacity has increased dramatically. The pandemic, global supply chain disruptions, and skilled-worker shortages aggravate the situation.

But, if taken as a given, the fact that film is not a “cheap alternative” to anything is not necessarily bad. Film is a legitimate imaging medium that continues to be used not only for everyday personal snapshots and by hobby photographers, but also increasingly by professionals such as artists and commercial photographers. In the motion picture industry, film is more popular than ever, especially with fashion and music video productions, enabling looks that can set a production apart from its competition.

Why Film is Expensive

The manufacture of contemporary color films is a high-tech operation similar to semiconductor manufacturing – but even more complex! It is amongst the most complex chemical and industrial manufacturing processes devised to this day.

When the demand for photographic film peaked in the year 2000, behind it stood billions of dollars invested in research and development, and more than a hundred years’ worth of research done by some of the brightest minds of their generations. The manufacturing process for film is so complex, that even at its peak only four companies worldwide were able to produce a color film that met the highest quality standards: Eastman Kodak, Agfa-Gevaert, Konica, and Fujifilm. And in addition to being a very complex product, film requires many resources that are getting difficult and/or expensive to source, or that need to be reengineered because of valid environmental concerns.

For example, due to the increased interest in biodegradable plastics, the demand for the base on which film emulsion is coated on, cellulose triacetate, has skyrocketed; many industries have discovered the material as a well-suited form of biodegradable packaging material. For this reason, manufacturers find it increasingly hard to source the material at acceptable prices, forcing them to substitute the film base with other materials like PET, or as it is known in the Kodak universe, with ESTAR base. Similarly, the price for silver, a crucially important ingredient in every film — about one kilogram of silver is needed for every 3000 rolls of 135 / 36-exposure Portra films — has risen by 38% in the last five years alone. Lastly, the people who are able to perform the highly complex manufacturing process are getting older and need to be replaced while younger staff need to be trained, a circumstance that further reduces capacity and increases operating cost.

With the gigantic volumes of the 1990s a thing of the past, Kodak and Fuji cannot simply rely on producing all their needed materials by themselves, or on being able to get the best prices from suppliers because of the enormous quantity being bought. Similarly, manufacturing capacity is greatly reduced; the same machines that ran billions of miles of film cannot operate efficiently on the smaller scale needed for today`s stable, but smaller market. New materials, new machines, new operators, and new markets have led to new circumstances that don’t accommodate the economies of scale that were at work in the past when it came to manufacturing photographic film.

But how does that affect film prices? “Back in the good old days, film was dirt cheap. Nowadays it costs an arm and a leg,” some might interject. As with many things, the truth about film prices lies somewhere in between rosy visions of days past and dissatisfaction with contemporary trends. Film cannot be produced as cost-effectively as in the past, and due to shortages in both personnel and material, film cannot be made quickly enough to meet demand and is thus in short supply; therefore, prices have risen.

Kodak, in particular, faces additional challenges. When speaking of film manufacturers, we often envision one company making and distributing film. But a unified Kodak company suppling film is no more: since the 2012 filing for bankruptcy protection, the company that manufactures the film is Eastman Kodak in Rochester, United States, and the company selling film for still photography is Kodak Alaris in Hemel Hempstead, United Kingdom. Each company is affected by the circumstances of the other. If Eastman Kodak increases its prices, Kodak Alaris must pass on this price increase to customers.

But at the end of the day the question is, how much have prices really risen? How do today’s film prices compare to those of other decades?

Is Film Too Expensive?

As a result of the digital revolution, film was sold disproportionately cheaply for about a decade, between 2005 and 2015. Towards the beginning of the new millennium film sales started to decline, slowly at first, and then more rapidly as of 2004. Manufacturers tried to stay competitive by lowering their prices, sometimes way beyond profitable, or even break-even levels, just to generate incoming cash flow. The first victim of this downward spiral was Agfa. The second one was Kodak. Then came Ilford. Fujifilm diversified and survived, even thrived. But despite all reassurances, there are signs that they may now be in the process of abandoning photographic film for good.

In the aftermath of the crisis that hit the analog imaging industry, the shards were picked up; Ilford was bought, Kodak survived its close shave with bankruptcy, and production of film continued at a lower and still declining level. Little new staff were trained or hired, and old engineers, chemists, and workers left, taking with them their valuable knowledge. Likewise, machinery was either demolished, neglected, or run into the ground and then not replaced. It seemed like the industry was finally winding down.

But it didn’t. With the reemerging interest in all things analog, the film industry, too, has experienced a revival of sorts. A glance at the current career page of Eastman Kodak’s website will even show film-related positions that come with a sign-on bonus of up to 1500 USD for candidates willing to work the night shifts at a converting line, where films are slit and perforated. Kodak is investing heavily, not only in new personnel, but into machinery as well. Investments that buy a future for film come with a price-tag that, sadly, will have to be paid by consumers. But to accurately gauge how much today’s film consumers are really supporting their film manufacturers, a look into the past can provide valuable insights.

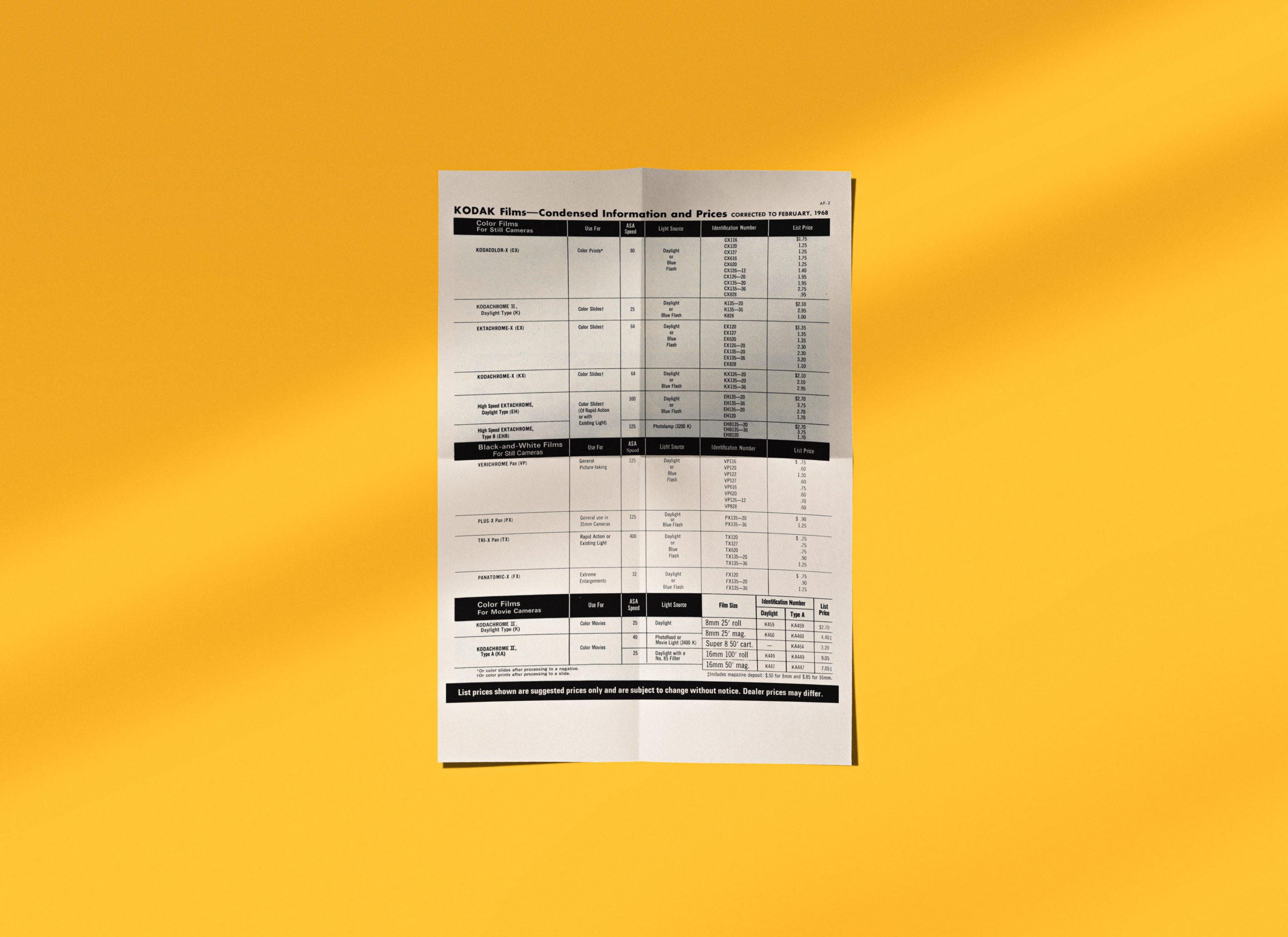

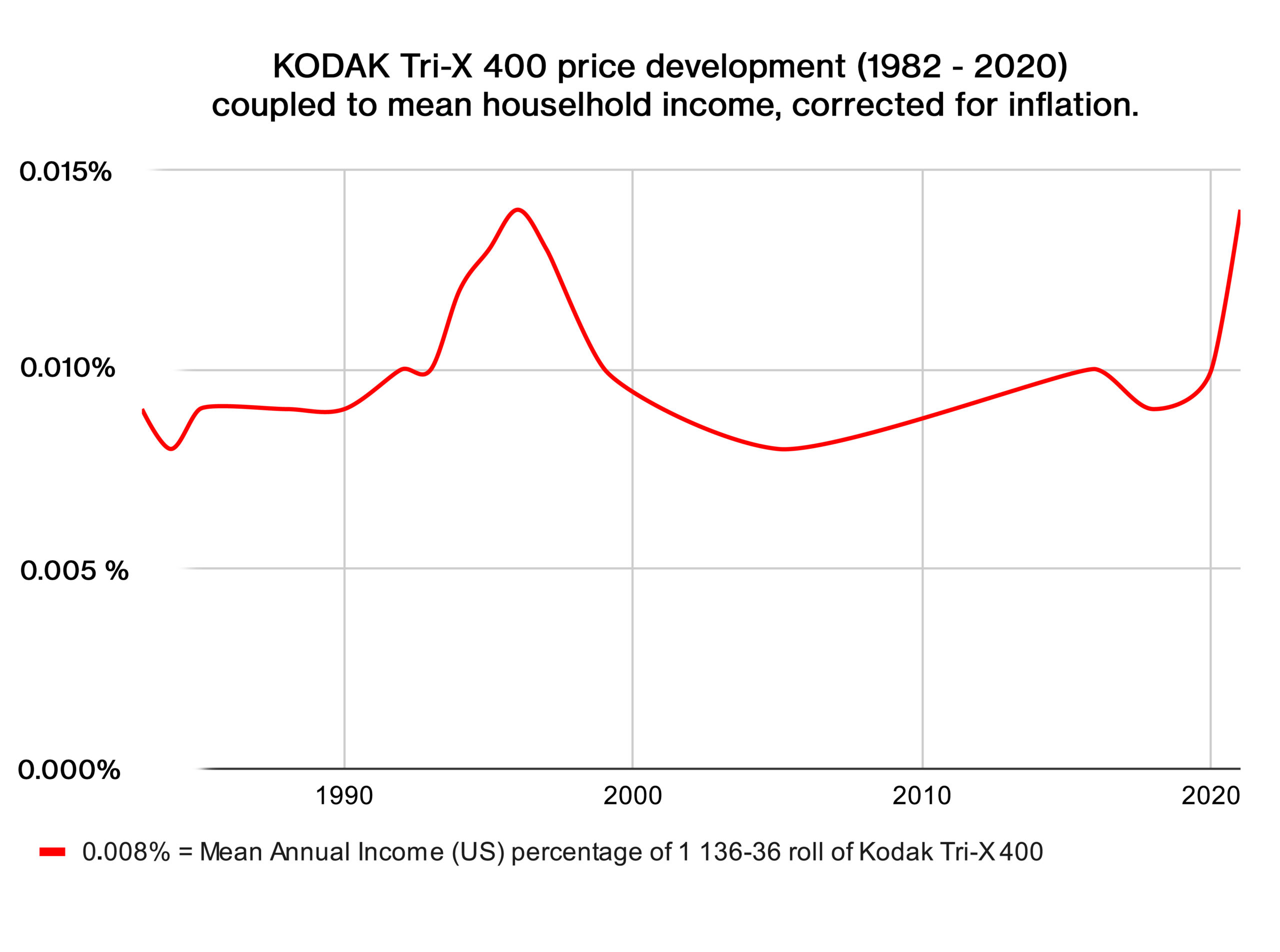

For the following comparison, real-world film prices from the last forty years were gathered from consumer catalogs and advertisements of large distributors like B&H, Adorama, and Freestyle. Averages were taken from multiple sources, where available. To make the data accessible and enable a comparison, all prices have been adjusted for inflation (unadjusted prices are in parentheses) and represent the 2021 US Dollar with a current inflation of 5.39 %. Historic data was sourced from the U.S. consumer price index and then coupled to mean household income to provide more relevant information regarding buying power and true cost of film in relation to income. While other films have been taken into consideration, the basis of the following analysis are prices for 135 / 36 cartridges of Kodak Tri-X.

In the last 40 years (not considering the current year, which will be analyzed separately) film prices were at an average period high in 1996, with a roll of Tri-X coming at a cost of 7.68 USD (4.39 USD). The low point of the period between 1981 and 2021 was reached in 2005 at a price of 5.02 USD (3.69 USD) per 135 / 36 roll. In total, this represents a drop in price of 35% from 1996 to 2005. Since 2005, prices have steadily climbed back, reaching the 1996 level in 2019.

Coupled to mean household income between 1981 and 2021, a roll of TRI-X has always cost about the same, though, being priced at approximately 0.01 % of the relevant mean income, with a drop between 2003 and 2006, reflecting the pricing strategy employed at the time. In general, this means that film prices have been relatively stable over the years. Flicking through old catalogs can thus be a treacherous affair because it can evoke the notion of everything having been cheaper, even if it wasn’t.

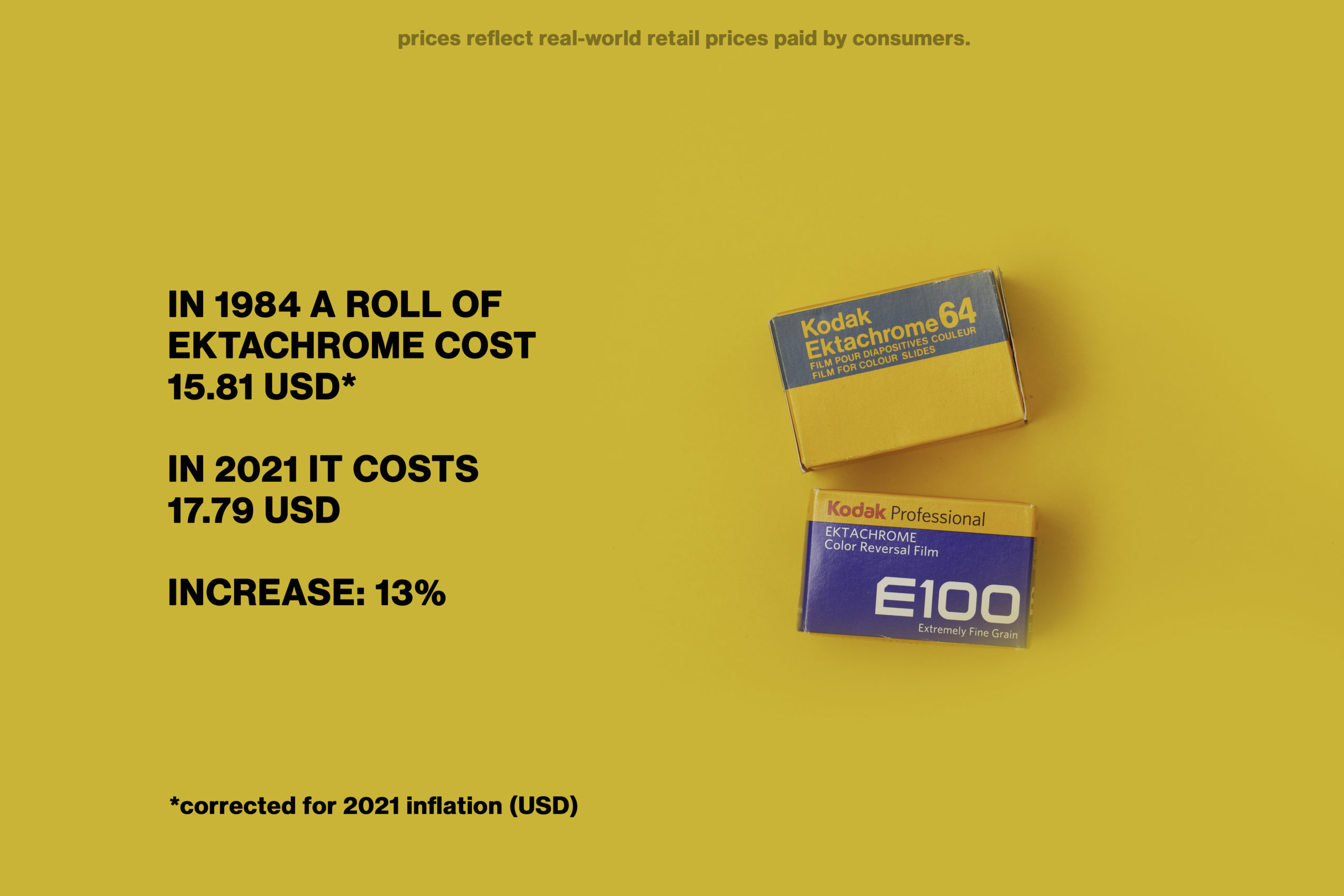

Another good example of the early 2000s price dump that puts current prices into perspective is Ektachrome silde film. For E100 (=EPP 100, E100G, E100VS) the cheapest prices for a 100 ASA professional Ektachrome film were taken as reference. In 1984, a roll of Ektachrome Professional 100 cost 15.81 USD (5.99 USD), which equaled 0.023% of the concurrent mean income, while at its all-time-low in 2005, its equivalent cost only 7.85 USD (5.59 USD) which equals only 0.012 % of the concurrent mean income.

With the most recent price increases, the price tag a consumer sees on a roll of film has become higher than at any time in the past 40 years. But even with the most notable increase which has come between 2020 and 2021, its price has not risen beyond comparison; the effective average price increase was around 30% in the period from 1981 to 2021. From a historical point of view, however, film is not more expensive than ever before, as some like to claim.

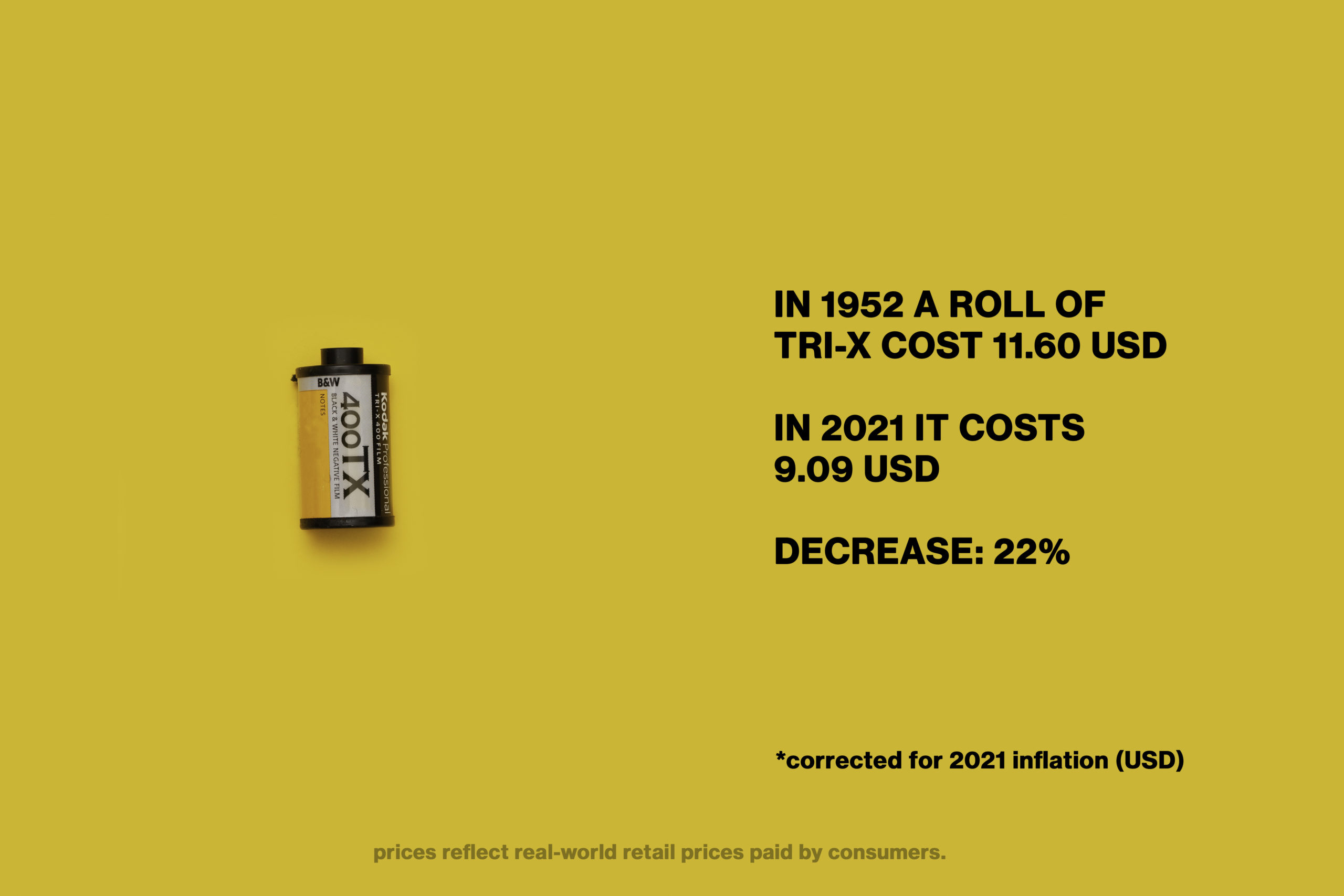

Put into the perspective of inflation and buying power, a 135 / 36-exposure roll of Kodak Tri-X cost 11.60 USD (1.15 USD) in 1956, and a roll of Kodacolor film even hit at over 22 USD (2.60 USD) back in the “golden age.” The current price of Tri-X, depending on reseller, is somewhere between 9.95 USD (B&H) and 9.09 USD (Freestyle) and thus roughly equals the pricing level of 1968, when Tri-X first flew to the moon on Apollo 8. Coupled to the 2020 US mean income, a roll of Tri-X is still at 0.012%, and thus not substantially more expensive than it was in the past.

Prices Have Risen, But Not Unprecedentedly High

While complaints about higher prices are understandable, and disgruntled feelings are shared almost universally — no one likes to pay more for a product that used to be cheaper — alarmism about film prices rising to the point of killing the analog revival are still out of proportion, though. Historic comparison shows that current prices are not unheard of. The economies of scale that were at work in the gigantic volume markets of the past are no more, and accordingly, prices have adjusted, too. For what it is, most film is priced appropriately. If there is any price gouging in analog photography, it isn’t committed by Kodak, Fuji, or Ilford, but by those resellers capitalizing on hoarded film they sell at astronomic prices to unsuspecting newcomers who are just starting out in analog photography.

If you like balanced and well-researched articles about analog photography similar to this one, consider subscribing to the print issue of SilvergrainClassics here: shop.silvergrainclassics.com/subscriptions/

You might also be intrested in this article on the subject of the Kodak price increase announced on November 4th 2020. see https://silvergrainclassics.com/en/2020/11/2021-kodak-film-price-increase-announced/