Poras Dhakan & “The Digital Passport Photo”

by Christopher Osborne.

Poras Dhakan takes a break from analog photography and contemplates his image through the medium of the digital passport photo

Poras Dhakan is an analogue photographer born in India and raised in the UAE. The son of Indian expatriates, Poras was educated in Sharjah and Britain, he practices law for a well-reputed law firm in the desert city of Dubai. He is a man of many parts, and in addition to being a registered Fairtrade jeweller, Poras is also an active analogue photographer.

He is currently studying an MFA in Photography at the University of Ulster, and that has in part lead him towards his current project which he examines his identity through the eyes of a digital camera, specifically through the eyes of the normally Indian run photo studios that are dotted across the region. This is part of his “Namak Halal” series (which translates to “Worth your salt”), where he explores the Indian expatriate, and particularly his own relationship with the region.

He dons a pair of overalls and walks into photo studios with a straight face and non-descript composure. English is the official second language of the Dubai Emirate, so when he explains that he needs a photo for a job application in Hindi, and then subsequently refuses to talk in English, he is positioning himself at the bottom of the social structure.

We talk more about the commissioning approach. The conversation begins with a reserved Poras saying that he needs a photo for a job application (in Hindi – “Bhaya, acha walla CV ke liye photo bana sakte ho”). By presenting himself in workers clothes, the assumption that he is already employed, but is about to lose his job. Perhaps the work he has been doing is coming to completion, or maybe the site is cutting back on staff? He could have even have just come from a one-sided argument with his boss? The question hangs over the studio like a cloud. He is non-committal to other questions. To questions like “should he wear a shirt and tie?” he simply shrugs and replies “just do what you think is best”.

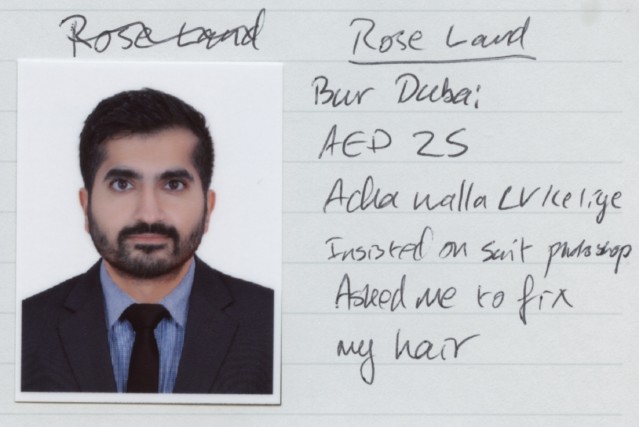

This is a work in progress and the images have been scanned directly from his workbook.

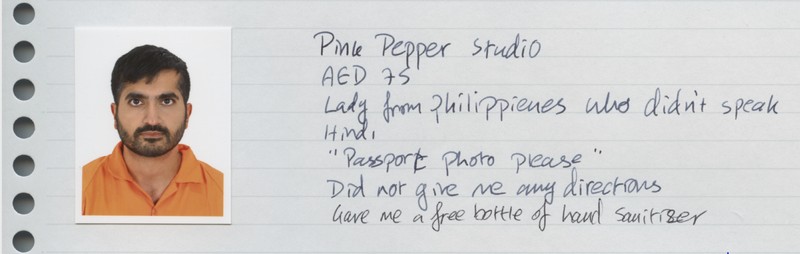

The first image was taken in a studio located in a suburban mall in a wealthy area. Poras explains that the Filipino lady who made the image was embarrassed that a worker was in the shop, and while she did not turn him away, equally, she could not have worked harder to have him in and out of the studio in record time.

We talked about his earnest expression. Poras describes his feelings at the time. “I felt nervous. I felt out of place walking into the mall in this outfit. And I imagine that this is exactly how a worker would have felt too”.

“I paid 75 dirhams (about $20.50) for the photograph. I was very conscious that I would never pay this much if I was the person I was pretending to be”, explains Poras.

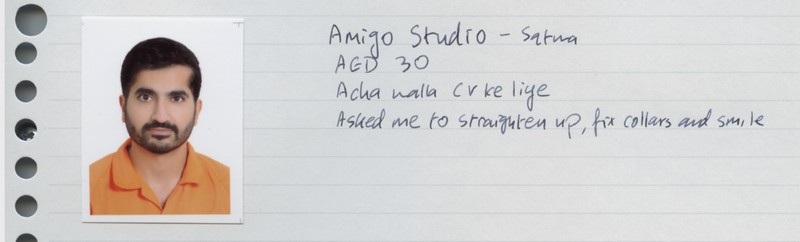

The next image was made at a studio in a poorer neighbourhood. He was made to wait 5 or 6 minutes before having his picture taken. The photographer spent a lot of time on his appearance. He was made to comb his hair three times and had his collar straightened. Then the photographer set to work on the image. His hair was changed, beard trimmed and chest hair removed.

“The photographer was dismissive but kindly. I felt as though he was trying to help me”.

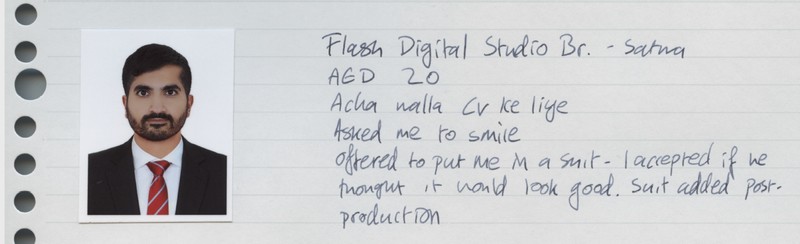

“The photographer of the third image went to town”, says Poras. He asked me to smile, but it must have been too much because he straightened the smile back out”. He added a suit in post-production. He had told me off for slouching three times, but in the final image, I have these amazing Clark Kent shoulders.

Poras’ girlfriend Hannah appears in the background. Hannah is from Bochum, Germany, and I ask her how she views the project. “I find it upsetting that people would want a face to be lighter. In Europe, I wouldn’t expect this, but here in the Middle East, this is daily life. Indian photographers just do it. It is what is expected”.

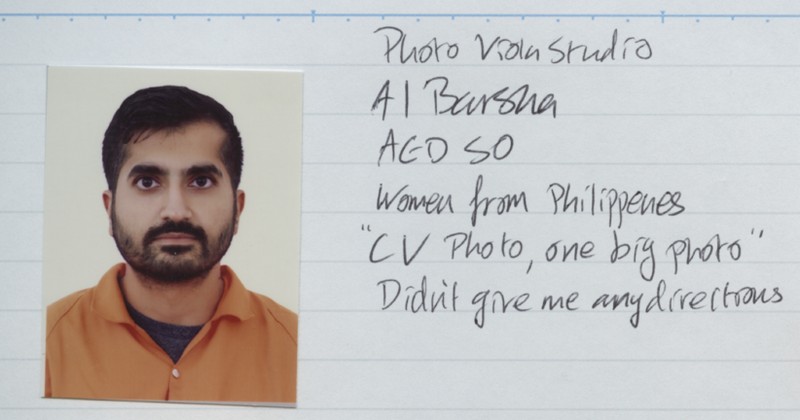

The image made at a studio in the Al Barsha district is the truest to life. The photographer seemed to feel “what does this guy care?”, and I had no input to the choice of image.

In contrast, in the majority of the Indian run studios, we selected the photograph together. It was a much more collaborative process. I was made to feel that I was part of the community and even if I was down on my luck that I was being looked after as one of their own.

The final image was made by an African woman. There were signs proudly promoting the fact that they had a lady photographer. “She didn’t fix me too much”, Poras explains. “It is by far the worst photoshop job. It was the Indian manager who instructed her to transform Poras into a suit. There was a whole wall of shirt, suit and tie combinations that you could choose from.

I ask Poras what he thinks about the results. “I find it really confusing. I walk out of the studios, and I look at the photographs trying to work out what the photoshop technician or photographer has changed. When I get home, I look in the mirror, and it is a shock. I have a moment where I am trying to work out which portrayal is real!

I am in Germany and Poras is in Dubai. We are talking over Zoom, and without realizing the significance of what he is saying, Poras nonchalantly reflects on the fact that even this platform portrays him with a lighter skin…

Images © Poras Dhakan 2021. You can see more of Poras Dhakan’s work on Instagram at @baked_with_light

We have a favour to ask. We want to make these online articles free to the world. We see it as our contribution to the photographic community. You can help by subscribing to our awesome analogue photography magazine – https://shop.silvergrainclassics.com/subscriptions/